Home » Posts tagged 'International Students'

Tag Archives: International Students

Meeting the International Student Enrolment Challenge with Enhanced International Student Engagement

Canada has seen a 29% increase in international students attending higher educational institutions, from 2022 to 2023, which has followed a 63% growth over the previous five years and more than 200% over the last decade (CBIE, 2023). This, however, is changing. Universities Canada (The Canadian Press, 2024) reports that enrolment of international students fell in 2024, in some cases by more than 50%, below the international student visa cap set by the federal government. Given this trend, we must ensure academic success and beneficial, appropriate, and resourceful study conditions for the international students studying at our institutions. One of the best ways of doing this is by enhancing international student engagement. In this blog, I introduce this topic and discuss ways we can all increase the engagement of international students in our classrooms.

International student engagement is international students’ active, ongoing effort to navigate and mediate the expectations and practices of their new academic environment (Kettle, 2017; Zimmerman, 2021). This concept views engagement as a social practice, where students interact with and respond to various elements such as actions, interactions, objects, values, expectations, and language. It emphasizes the students’ roles as active participants and experts in their own educational experiences, highlighting their strategies to adapt, succeed, and contribute to their academic and social environments. International scholarship on teaching and learning research shows that when international students feel connected and supported, they are more likely to dive into classroom activities, perform better academically, and build positive relationships with classmates and instructors (Freeman et al., 2014; Glass et al., 2015), and that engagement in the classroom is the strongest predictor of cognitive development for international students (Grayson, 2008).

Four interrelated types of engagement occur during learning activities, including behavioural, emotional, cognitive, and agentic engagement (Christenson et al., 2012). Behavioural engagement has been defined as participation in various activities (Finn, 1989), students’ positive effort, attention, and involvement in school (Skinner et al., 2009), and adaptive and maladaptive behaviour (Martin, 2010). Emotional engagement is generally conceptualized as comprised of positive and negative feelings toward school, teachers, and peers (Fredericks et al., 2004). Cognitive engagement has been described as beliefs and values about the importance of school and learning (Appleton et al., 2008; Martin, 2007) and self-regulation, strategy use, goals, and exerting effort (Martin, 2007). Agentic engagement is when individuals try to actively enrich their learning experiences and take responsibility for them (Reeve & Tseng, 2011).

Sense of belonging in a higher-educational setting significantly impacts the engagement of international students (Cena et al., 2021; Glass et al., 2015). Previous studies have shown that international students report a lower sense of belonging than native students (Strayhorn, 2012; Van Horne et al., 2018), and that the type and amount of extracurricular/social involvement are related to the sense of belonging (Bowman et al., 2019; Maestas et al., 2007), with more frequent participation in extracurricular activities increasing the sense of belonging to the institution (Thies & Falk, 2023). International students who feel integrated into the university community through meaningful interactions are more likely to participate in social activities (Glass et al., 2015).

Engagement is also affected by students’ unwillingness to communicate, which is the long-term tendency to avoid and/or devalue verbal communication (Kadi & Madini, 2019). Several factors related to anxiety have been identified, including concerns that limited English-speaking proficiency can inhibit clarity (Aksak & Cubucken, 2020; Horwitz et al., 1986), fear of being humiliated (Chichon, 2019; Wen & Cle ́ment, 2010), lack of self-confidence (Kadi & Madini, 2019; Saadat & Mukundan, 2019), anxiety over potential errors (Kang, 2005), instructors’ excessive emphasis on grammar (Wen & Cle ́ment, 2003; Woodrow, 2006), and place of origin (Woodrow, 2006). Several motivation and related factors have been identified as engagement influencers, including personality (Hz, 2022; Mohammadian, 2013), discussion topic (Kang, 2005; Zhou et al., 2021), grade evaluation approach (Zhou et al., 2021), family support (Aksak & Cubucken, 2020; Aydin, 2017), and socialization demands (MacIntyre et al., 1998).

Institutional policies and practices, such as inclusive teaching practices, culturally sensitive curricula, and opportunities for social interaction, play a pivotal role in fostering student engagement (Glass et al., 2015). Instructors can engage in strategies to enhance in-class communication, including shaping a positive classroom environment that can relax international students and reduce their anxiety (Smith et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2021), developing workloads appropriate for international students (Zhou et al., 2021), adopting collaborative teaching approaches (Lee et al., 2019; Saadat & Mukundan, 2019; Zhou et al., 2021), involving students in peer teaching (Freemen et al., 2015; Yamauchi et al., 2016), engaging in problem-based learning to encourage students to solve real-world problems in collaborative settings (Freemen et al., 2015; Yamauchi et al., 2016), using group discussions for students to articulate their understanding, ask questions, and learn from their peers (Freemen et al., 2015; Yamauchi et al., 2016), preparing before class to expand their knowledge of students’ cultural backgrounds and traditions (Riasati, 2012; Zhou et al., 2021), conducting warm-up activities at the beginning of class (Zhou et al, 2021), applying supportive practices (Kinsella, 1997; Smith et al., 2019), and using culturally-responsive teaching methods (Gay, 2010; Zhou et al., 2017).

So, while we could lament the current decrease in international student enrolment facing most Canadian post-secondary educational institutions, there is much we can and should do to increase international student engagement leading to higher levels of success for those students able to enrol at our institutions despite the current regulatory approach to cap international student enrolments.

References:

Aksak, K., & Cubukcu, F. (2020). An exploration of factors contributing to students’ unwillingness to communicate. Journal for Foreign Languages, 12(1), 155-170. https://doi.org/10.4312/vestnik.12.155-170

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 369-386.

Aydın, F. (2017). Willingness to communicate (WTC) among intermediate-level adult Turkish EFL learners: Underlying factors. Journal of Qualitative Research in Education, 5(3), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.14689/issn.2148-2624.1.5c3s5m

Bowman, N, A., Jarratt, L., Jang, N., & Bono, T. J. (2019). The unfolding of student adjustment during the first semester of college. Research in Higher Education, 60(3), 273-292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9535-x

Canadian Bureau of International Education (2023). International students in Canada, https://cbie.ca/infographic/

Cena, E., Burns, S., & Wilson, P. (2021). Sense of belonging and intercultural and academic experiences among international students at a university in Northern Ireland. Journal of International Students, 11(4), 812-831. https://www.ojed.org/index.php/jis/article/view/2541

Chichon, J. (2019). Factors influencing international students’ willingness to communicate (WTC) on a pre-sessional programme at a UK university. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 39, 87-96.

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Springer Nature. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-031-07853-8.pdf

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59, 117 – 142.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Glass, C. R., Kociolek, E., Wongtrirat, R., Lynch, R. J., & Cong, S. (2015). Uneven Experiences: The Impact of Student-Faculty Interactions on International Students’ Sense of Belonging. Journal of International Students, 5(4), 353-363. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1125097.pdf

Grayson, J. P. (2008). The experiences and outcomes of domestic and international students at four Canadian universities. Higher Education Research & Development, 56, 473-492.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern language journal, 70(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

Hz, B. I. R. (2022). Exploring students’ public speaking anxiety: introvert vs extrovert. Journal of English Language Studies, 7(1), 107–120. https://jurnal.untirta.ac.id/index.php/JELS/article/view/14412/8831

Kadi, R. F., & Madini, A. A. (2019). Causes of Saudi students’ unwillingness to communicate in the EFL classrooms. International Journal of English Language Education, 7(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijele.v7i1.14621

Kettle, M. (2017). International student engagement in higher education: Transforming practices, pedagogies and participation (pp. 5, 09-11, 13, 12, 11). Multilingual Matters. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/103570/22/103570.pdf

Kinsella, K. (1997). Creating an enabling learning environment for non-native speakers of English. In A. I. Morey, & M. K. Kitano (Eds.), Multicultural course transformation in higher education: A broader truth (pp. 104-125). Allyn and Bacon.

Lee, J. S., & Lee, K. (2019). The role of self-efficacy, task value, and learning goal orientation in willingness to communicate in a second language. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 40(2), 140-156.

Lee, J. S., Lee, K., & Chen Hsieh, J. (2019). Understanding willingness to communicate in L2 between Korean and Taiwanese students. Language Teaching Research, 26(3), 455-476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168819890

Macintyre, P. D., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a l2: A situational model of l2 confidence and affiliation. The Modern Language Journal, 82(4), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x

Maestas, R., Vaquera, G. S., & Zehr, L. M. (2007). Factors impacting sense of belonging at a Hispanic-serving institution. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 6(3), 237-256. http://doi.org/10.1177/1538192707302801

Martin, A. J. (2007). Examining a multidimensional model of student motivation and engagement using a construct validation approach. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 413-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000709906X118036

Mohammadian. T. (2013). The effect of shyness on Iranian EFL learners’ language learning motivation and willingness to communicate. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(11), 2036-2045. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.11.2036-2045

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

Riasati, M. J. (2012). EFL learners’ perception of factors influencing willingness to speak English in language classrooms: A qualitative study. World Applied Sciences Journal, 17(10).

Saadat, U., & Mukundan, J. (2019). Perceptions of willingness to communicate orally in English among Iranian PhD students. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 8(4), 31-44. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.8n.4p.31

Skinner, S., Kindermann, T., & Furrer, C. (2009). A Motivational Perspective on Engagement and Disaffection Conceptualization and Assessment of Children’s Behavioral and Emotional Participation in Academic Activities in the Classroom, Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493-525.

Smith, C., Zhou, G., Potter, M., & Wang, D. (2019). Connecting Best Practices for Teaching Linguistically and Culturally Diverse International Students with International Student Satisfaction and Student Perceptions of Student Learning, Advances in Global Education and Research Volume 3 (James, W. B., & Cobonoglu, C., Eds.), pp. 252-265. Association of North America Higher Education International.

Strayhorn, T. L. (2012). Sentido de pertenencia: A higherarchical analysis predicting sense of belonging among Latino college students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 7(4), 30-320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192708320474

The Canadian Press (2024, August 30). International student enrolment drops below federal cap: Universities Canada. National Post. Retrieved from https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/international-student-enrolment-drops-below-federal-cap-canada?taid=66d1bed289440d0001d0b514&utm_campaign=trueanthem&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter

Thies, T., & Falk, S. (2023). International students in higher education: Extracurricular activities and social interactions as predictors of university belonging. Research in Higher Education, 2023. https://doi-org.ledproxy2.uwindsor.ca/10.1007/s11162-023-09734-x

Van Horne, S. V., Lin, S., A. M., & Jacobson, W. (2018). Engagement, satisfaction, and belonging of international undergraduates at U.S. research universities. Journal of International Students, 8(1), 351-374. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v8i1.169

Wen, W. P., & Clément, R. (2003). A Chinese conceptualisation of willingness to communicate in ESL. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 16(1), 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310308666654

Woodrow, L. (2006). Anxiety and speaking English as a second language. RELC Journal, 37(3), 308–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688206071315

Yamauchi, L. A., Taira, K., & Trevorrow, T. (2016). Effective instruction for engaging culturally diverse students in higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 28(3), 460-470.

Zhou, G., Liu, T., & Rideout, G. (2017). A study of Chinese international students enrolled in the master of education program at a Canadian university. International Journal of Chinese Education, 6(2), 210-235. https://doi.org/10.1163/22125868-12340081

Zhou, G., Yu, Z., Rideout, G., & Smith, C. (2021). Why don’t they participate in class? In V. Tavares (Ed.), Multidisciplinary Perspectives on International Student Experience in Canadian Higher Education (pp. 81-101). IGI Global, https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-5030-4.ch005

Zimmermann, J., Falk., S., Thies, T., Yildirim, H. H., Kercher, J., & Pineda, J. (2021). Spezifische Problemlagen und Studienerfolg internationaler Studierender [Specific challenges and study success of international students]. In M. Neugebauer, H.-D. Daniel, & U. Wolter (Eds.): Studienerfolg und Studienabbruch (pp.179–202). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-32892-4_8

Student Perspectives on the Promising Practices for Teaching International Students

In our 2022 IGI-Global book, Handbook of Research on Teaching Strategies for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students, we explored the promising practices for teaching linguistically and culturally diverse international students by providing the student voice on such topics as culturally responsive education, pedagogy internationalization, teaching about academic integrity, student development and support, and online teaching and learning.

In our foundational work, we conducted a mixed methods study that reviewed the promising teaching practices to teach international students by evaluating the rate of student-satisfaction levels and perceptions of learning (Smith et al., 2019). The research design included a pilot study, an online survey questionnaire, focus-group discussions, and individual interviews. Research participants, with a response rate of 32 percent, were international students who studied at a mid-sized, comprehensive, public university in Canada. The primary research question is: What promising teaching practices yield high levels of international student satisfaction and perceptions of learning?

It was guided by three theories (Figure 1). The primary theory used is Tinto’s (1993) student integration model, which states that students must integrate into both social and academic settings, formally and informally, to create a connection with their postsecondary institution, resulting in them making a commitment to careers and educational goals. The researchers also relied on the work of Darby and Lang (2019), which highlights the connection between instructor personality and learning, and Tran’s (2020) framework for teaching and learning for international students, which underlines the importance of connecting with academic and social experiences.

Figure 1. Identifying Effective Teaching Practices (Smith et al., 2019)

Promising teaching practices received from respondents, that were reported as satisfied or very satisfied, varied from 49.7% to 82.9%. The teaching practices with the highest respondent satisfaction percentages (greater than 70%) fell into eight areas (Figure 2): academic integrity, assessment, assignments, clarifying expectations, communicating outside of the classroom, lecture design and delivery, verbal communications, and visual communications. All the promising teaching practices identified as having high levels of student satisfaction also have medium or high student perception levels of learning.

Figure 2. The Top Eight Promising Teaching Practices (Smith et al., 2019)

In the focus group and interviews (Figure 3), students’ responses were mainly positive. Most of them identified instructors as a key factor in the learning experience. Some characteristics (e.g., humour, encouragement and support, and the value of diverse cultures) were welcomed by students. Many practices were endorsed by students of all educational levels, including a student-centred approach, the use of interactive teaching methods, specific and prompt feedback, the use of practical experiences, a pleasant learning environment, and methods to support additional language learners. Undergraduate participants were interested in academic support, updated curricula, and partially filled slides in advance of class. They also emphasized the importance of experiential and applied learning, and close interaction with instructors. Graduate students spoke of the importance of a free learning environment, multi-modality teaching strategies, the use of digital and visual materials, and emotional, physical, and non-judgmental support from their supervisors. Teaching methods that led to students becoming bored and having heavy workloads, such as grammar-intensive teaching, and the use of the repeating-listening pattern of teaching and learning, along with a lack of encouragement, received dissatisfaction from students. There are some differences between course-based and research-based graduate student responses. Course-based graduate students commented on their course instructors and teaching methods, while research-based graduate students mostly commented on their relationship with supervisors.

Figure 3. Teaching practices that contribute the most to learning (Smith et al., 2019)

This study identified teaching practices that result in both student satisfaction and student perceptions of learning. Many students called for a multi-modal teaching style that combined traditional lectures and interactive methods. They also described some instructor characteristics as important factors in the student experience. Our research study found that the most promising teaching practices identified as having high levels of student satisfaction also have medium/high student perceptions of learning.

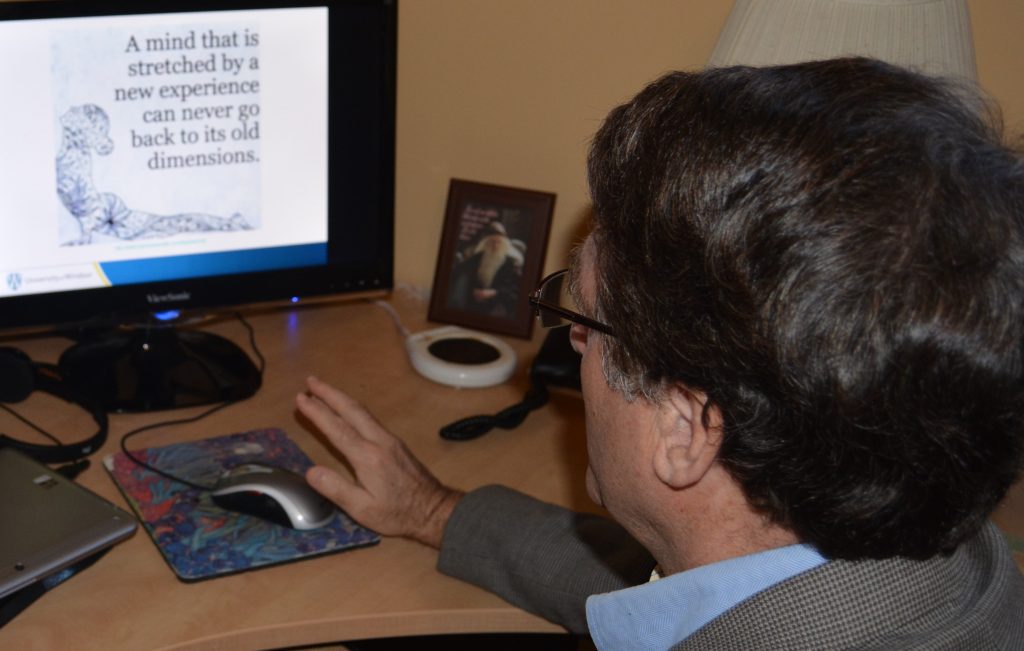

We are continuing our work through the creation of an online teaching international students website (https://teachintlstud.com/) that includes a professional development toolkit, resources for teachers, a professional community of practice, and a blog on teaching culturally and linguistically diverse students.

-Clayton Smith and George Zhou

REFERENCES

Darby, F., and Lang, J. (2019). Small teaching online. John Wiley & Sons.

Smith, C., Zhou, G., Potter, M., and Wang, D. (2019). Connecting best practices for teaching linguistically and culturally diverse international students with international student satisfaction and student perceptions of student learning. Advances in Global Education and Research, 3, 252-265. 24

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. University of Chicago Press.

Tran, L. T. (2020). Teaching and engaging international students: People-to-people connections and people-to-people empathy. Journal of International Students, 10(3), xii-xvii. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v10i3.2005

For more details on this study, see: Smith, C., & Zhou, G. (2022). Teaching culturally and linguistically diverse international students: Connections between promising teaching practices and student satisfaction. In C. Smith & G. Zhou (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching strategies for culturally and linguistically diverse international students (pp. 1-16). IGI-Global.

Pathways to Post-Pandemic Enrolment Growth in Higher Education

Recently, Stefanie Ivan, an enrolment management consultant and Royal Roads associate faculty, and I had an opportunity to facilitate a webinar on “Pathways to Post-Pandemic Enrolment Growth in Higher Education.” This is a follow-up webinar to the one we conducted on post-pandemic higher education enrolment trends (see my earlier blog) in February.

We asked participants to share their most effective strategic enrolment management (SEM) strategy efforts. We then asked them to describe strategies for enrolling and supporting international, Indigenous, and domestic learners. Lastly, we asked them to say a bit about the learner and student support they provided.

When asked to provide one word that describes the effectiveness of current SEM strategy efforts, the most frequently mentioned were disconnected, work-in-progress, and growing. Others identified include developing, unsure, hopeful but slow, disjointed, uninformed, innovative, ongoing, challenging, deepening, modest, and uncertain. It appears that the experience with SEM is quite variable with some saying it is stalled while others report it as in progress or growing.

We then asked about strategies in use to enrol/support specific types of students. Below are some of the comments we heard.

International Students:

- Work closely with our key agents and agent relations management; strengthen relational networks

- Develop a personal connection to the institution and community

- Targeting markets that connect with Canada’s labour shortage areas

- Provide incentives that are appealing to international students

- Optimize admissions processes

- Utilizing a group effort to recruit international students

- Develop personal communications

- Have not returned to accepting international students yet

Indigenous Students:

- Focused listening and working with communities to address their concerns and needs; engaging communities through partnerships

- Developed an Indigenous strategic plan

- Established an Indigenous scholars’ circle

- Increasing and deepening supports

- Going to communities with incentives, application forms, and testing formulas for completion on-site

- We are not currently recruiting Indigenous students

Domestic Students:

- Balancing in-person and online events

- More first-year transition strategies to help retention and success

- Target movement in the job market and second-career students

- Utilize a blended delivery model for full-time and part-time students

- Work toward understanding what students and employers

- Reach out to withdrawn student

- Establish better support services, create more webinars/engagement, partner with community organizations, and follow-up strategies

- Treat in-country ESL/ELL students as domestic prospects

Learner and Student Support:

- Online advising

- Development of non-academic learning communities

- Increased/streamlined communications (phone, email, forums, chatbot, extended hours, weekends)

- 1:1 wellness check-ins

- Alternative accommodations for learners who need it

- A strong return to in-person and social and co-curricular activities

- Entering students into classroom settings right away to determine learning needs

Here is the Video from the webinar.

With so much to do to stabilize and grow enrolments during these post-pandemic days, it will be important to be strategic and there is no better way to do this than through adopting and implementing SEM!

-Clayton Smith

Interrogating Race and Racism in Postsecondary Language Classrooms

Language is power, in the hands of linguistic gatekeepers and the dominant class. From “coloniality of power” (Quijano, 2000) to “coloniality of language” (Veronelli, 2015, p. 113), English has become a “colonial language” (Kachru, 1986, p. 5) and a “language for oppression” (Kachru, 1986, p. 13), replacing the implementation of carrots and sticks in the colonial times in the form of instilling raciolinguistic ideologies of the centre into the periphery. Language is raced and race is languaged (Alim et al., 2016). Racialization, synonymous with racial classification, is a process of “Looking like a Language, Sounding like a Race” (Rosa, 2019). The racialization of language subjugates, subordinates, dehumanizes, and others people of colour.

Join us as we interrogate race and racism in postsecondary language classrooms in our upcoming IGI-Global book. We will use the perspective of intersectionality between language and race in higher education classrooms, by problematizing raciolinguistic injustice and hierarchy with the monolingual and monocultural norm as a frame a reference, combating racism, linguicism, native speakerism, and neo-racism, as well as calling for changes, emancipation, and pedagogical paradigm shifts so as to teach English for justice and liberation (Huo, 2020). This book will investigate race and racism in postsecondary language classrooms, how race intersects with language, how power impacts and shapes language teaching and learning, and how hegemony and ideology perpetuate linguistic injustice and discrimination against racially minoritized students. It will examine how racism has created institutional, structural, and individual barriers for language learners in higher education, as well as potential strategies to combat racism, linguicism, and neo-racism.

We ask prospective contributors to submit research-based and data-driven chapters to elicit stories, counter stories, garner racialized experiences and perspectives, and represent resistant voices through multiple research methods, including but not limited to interviewing, observation, discourse analysis, narrative inquiry, ethnography, journaling, focus groups, surveys, and case studies. Here is the Call for Proposals.

Recommended Topics

- Race, racialization, and racism

- Intersectionality between race and language

- Language and identity

- Linguicism and linguistic imperialism

- Monolingualism, native speakerism, and standardization

- Native-non-native dichotomy

- Power, hegemony, and hierarch

- Raciolinguistic ideology

- Neo-racism (i.e., based on nationalities, ethnicities, and cultures)

- Accentism

- Language diversity and linguistic rights

- Raciolinguistic justice and social justice

- Discourses and stories in different geographic and language teaching contexts across the globe

- Narratives and counter-narratives

- Barriers, challenges, and resistance

- Lived experiences

- Multilingualism, plurilngualism, and translanguaging

- Anti-oppressive and decolonizing language policies

- Anti-racist and anti-colonial pedagogies and practices

- Critical pedagogies in global higher education language teaching contexts

- Ethical internationalization in postsecondary language classrooms

This book is intended for scholars, researchers, faculty, instructors, and professionals in English language teaching, higher education, language education, applied linguistics, sociolinguistics, educational linguistics, anti-racist education, critical multilingual studies, translingual studies, and those who are interested in the research of race, language, and the area of teaching English cross-culturally and translingually in higher education classrooms, such as faculty and instructors, educational developers who design the inclusive, anti-racist, and anti-colonial curriculum, and administrators and policymakers who oversee academic, especially language programs. The book will also be useful for teacher candidates, non-native English-speaking students, undergraduates, and graduate students in TESOL/ESL, second language acquisition, and higher education programs.

Important Dates

- March 31, 2023: Proposal Submission Deadline

- April 14, 2023: Notification of Acceptance

- May 14, 2023: Full Chapter Submission

- June 27, 2023: Review Results Returned

- August 8, 2023: Final Acceptance Notification

- August 22, 2023: Final Chapter Submission

If you would like to discuss a potential book chapter idea, contact us at raceandlanguage@gmail.com.

-Xiangying Huo (University of Toronto) and Clayton Smith (University of Windsor)

References

Alim, S., Rickford, J. R. & Ball, A. F. (Eds.) (2016). Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Huo, X. Y. (2020). Higher education internationalization and English language instruction: Intersectionality of race and language in Canadian universities. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-60599-5

Kachru, B. B. (1986). The alchemy of English: The spread, functions and models of non-native Englishes. Pergamon.

Quijano, A. (2000). The coloniality of power and social classification. Journal of World-Systems Research 6(2), 342-386.

Rosa, J. (2019). Looking like a language, sounding like a race: Raciolinguistic ideologies and the learning of Latinidad. Oxford University Press.

Veronelli, G. A. (2015). Five: The coloniality of language: Race, expressivity, power, and the darker side of modernity. Wagadu: a Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies, 13, p. 108-134.

University Degree v. University Education

In this blog, I share thoughts written by Shaun Smith, a recent University of Windsor graduate, on the differences between a university degree and a university education. It is inciteful and will likely result in some important reflections being made on the university student experience.

-Clayton Smith

Six years ago I sat in a large classroom surrounded by other recently-graduated high school students entering my program and listened to one presenter after another speak a variation of the same thing, “I wish I’d gotten involved sooner.” These presenters themselves were older students, about to leave university and go on either into the workforce or further education, and at the time, I couldn’t fully comprehend what exactly it was that they were attempting to say. One completed undergraduate degree later, when I was working with incoming high school students myself, I found myself telling them the same thing I had been told when I was in their position.

What these presenters by and large were saying as a collective was that they felt as though they had missed out on certain aspects of university life early in their time on campus. That their hesitation to reach back when the opportunities reached out had cost them in various personal, academic, and professional ways. It was only later, in their third or fourth years, did they fully take advantage of these opportunities.

Despite the advice of the presenters, my time in university began to play out in a very similar way. I was a commuter student, whose first-year mandatory classes were organized by my faculty to be in convenient windows of time (e.g. 8:30 AM-1 PM), which meant that outside of these windows, I perceived there to be little reason why I should remain on campus. Certainly, my fellow students also felt this way, as our faculty building was virtually deserted after 3 PM every day, when the final class had ended. As a true commuter student, I went to campus for class, and left as soon as I could. That pretty accurately describes the first two years of my undergraduate, I even studied at home, or with one or two of my classmates off-campus.

Said differently, I was in the process of earning a university degree. My grades were good, and I had worked hard enough in my second year that my name showed up on the Dean’s List for the first time. By any academic measure, I was well on track to graduation.

In third-year, however, something changed. Although I had a reasonably positive and fulfilling social life (primarily off-campus), the decision was made to make more of an effort on campus as well. I had always played intramural sports, but now I found myself hanging out with the people I knew there outside of the gym or soccer pitch, which opened up an entire community to me (who wound up becoming an incredible source of social support for me during the COVID-19 pandemic). I had always done due diligence in my classes, but when a professor asked if any of us were interested in competing in a case competition at another university, this time I thought, “why not?” instead of “that’s not for me.” Instead of leaving campus when my classes were completed, I began to actively look for things to do, which resulted in me doing everything from judging academic debates to participating in mental health initiatives for faculties that were not even my own. I went to buildings on campus I never had before through electives that I found genuinely fascinating, and unlike my first two years, actually made an effort to be a part of those groups instead of dipping upon the conclusion of the class. This, for the first time, actually opened up the entire university to me as opposed to just my own department.

I could go on, but for the sake of brevity, will instead summarize by saying that this was every day. My university experience went from a primarily class-based academically grounded experience to a socially diverse and entirely unpredictable day-to-day experience with people I perhaps had just met that morning, doing activities that the previous version of myself could not have possibly seen himself participating in.

Perhaps this sounds stressful. Perhaps it seems as though my academics would suffer, that this spontaneity where I departed my home every morning having no idea how the day would play out could only create harm towards the goal that every student has when they first come to university: the degree.

The complete opposite was true.

I became significantly happier. My grades skyrocketed. I went from being an above-average student to one of the best in my faculty. I made friends from every corner of campus, and because of the international nature of the university, every corner of the world. My professors not only learned my name, but began offering research opportunities and academic-related guidance that had always been there, but I hadn’t previously had the gumption to take advantage of. For the first time, I realized what those senior students had been trying to convey – that there is a significant difference between a university degree and a university education.

A university degree is something we all know. It’s a piece of paper that signifies that an individual has undergone an accepted curriculum and passed. But that’s all it is.

University education is something else entirely. Yes, it is everything that happens inside of the classroom, but more importantly, it’s everything that happens outside said classroom.

When I graduated from university, I had a collection of skills that I had learned there, but the vast majority of them I obtained from the education, not from the degree. The university degree taught me important skills: work ethic, consistency, specialized knowledge, and showing up. The university education taught me everything else.

When I took part in the “real world” this collection of skills proved invaluable. Interpersonal dynamics in particular have played a strong role, and the social environment of a diverse campus is the perfect place to cultivate such a skill. Of course, there are skills beyond that that has drastically improved everything from my overall adaptability in both professional and personal situations. Everything from my public speaking to my comfortability with challenging my own worldview has its root in my university education.

If this is still somewhat unclear, refer to the age-old conflict between intelligence and wisdom. If intelligence is the presence of knowledge, and wisdom is the ability to apply it, the university degree is the presence of knowledge in an individual, and the university education is the skills from which one can apply that knowledge most effectively.

Even as a student I became aware of all this. The question following my third year was how to maximize this education while I still was in the opportunity-laden university environment. For me, it resulted in my going on a student exchange to Belgium (something that I in my first-year would have been both impressed and terrified by) for my final undergraduate year. To say that it was stepping outside of my comfort zone is the understatement of the century, but it certainly maximized the university education aspect, and I look back on years three and four as the best of my life…so far.

Fast-forwarding to the current day, as I apply for positions and look to start what I hope is a long and successful professional career, I am often relying on my university education, and my prospective employers are too. No HR or management person has cared one bit what my GPA was, in fact, I’ve never been asked. However, they care very strongly about one’s ability to solve their problems, and very rarely is that solution specialized knowledge. It is instead one’s ability to problem solve complex and ever-evolving challenges and to be able to do so as part of some type of team.

My university degree prepared me only in part for that. My university education absolutely finished the job.

-Shaun Smith

Scary and Fascinating: Online Teaching in Challenging Times

Have you ever started writing on a topic and then something happens that changes everything? Well, that just happened to me. About a month prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, I was writing on the growing interest in and support for open and online learning in postsecondary education. Then poof! COVID-19 changed everything. Today I will share with you some of my initial thoughts on this topic and then reflect on how the events of the last month changed some of my thinking.

Here are some of my initial thoughts.

Following completion of the University of Windsor Office of Open Learning’s Certificate of Online and Open Learning and attendance at eCampusOntario’s Technology + Education Seminar + Showcase (TESS) conference, I initiated a study to explore the connection between the promising practices for teaching online linguistically and culturally diverse international students and student satisfaction and student perceptions of learning, which has recently received research ethics approval but is now paused. An overview of this study is available on my faculty web page. Also, working with two University of Windsor colleagues (Mark Lubrick and Carson Babich), I oversaw the writing of my first Open Educational Resource textbook (Leadership and Management in Learning Organizations), which we hope to publish in the next few months. All of this opened my eyes to the possibilities of online learning within the higher education sector.

And then, just before the pandemic broke, I enjoyed reading the Wiley Education Services study, “Student Perspectives of Online Programs: A Survey of Learners Supported by Wiley Education Services” (Magda & Smalec, 2020), in which student satisfaction with online learning was explored at 19 institutions where students were enrolled in Wiley-supported programs. The study provided some fascinating insights that showed ways to better meet student needs and expectations, including examine the complete student journey to remove barriers to flexibility, create a consistent learning experience to alleviate unneeded stress, and empower faculty to engage with students to improve the learning experience.

And here is a little of what we knew about online learning in North America before COVID-19.

North American online education has seen a rise in popularity in recent years. The Canadian Digital Learning Research Association reported that Canadian postsecondary online course registrations grew by 10 percent in 2018 and 2019, and most institutions expect enrollments to increase in the coming year (Johnson, 2019). The U.S.-based National Center for Education Statistics (Ginder, Kelly-Reid, & Mann, 2017) reported that the number of students who take at least some of their courses online grew by 5.7 percent in 2017. More than 25 percent of students take at least one online course during their time at university of college (Cook, 2018). Undergraduate international students attending Canadian institutions are increasingly choosing to take online courses (Best Colleges, 2019; Thomson, & Esses, 2016).

And here is some of my thinking since COVID-19 joined our world.

Like most faculty, I found myself scrambling a bit to convert my in-person courses, some of which were hybrid courses, to fully online courses. With lots of support from our Office of Open Learning and Centre for Teaching and Learning, as well as experienced colleagues, I made the leap. It was a bit scary, but also fascinating.

On the scary side, there is me. While I had recently acquired professional development in open and online learning, I am an in-person educator who greatly enjoys the interaction with students. Seeing their smiles and their fears is a big part of how I ensure a learning-centred classroom environment. When this all moved to being digital, I, like many of my colleagues, was petrified. Then there are my students, who were equally scared since all of this happened within the last three weeks of the semester. Fortunately, our university put in place a flexible approach that included assessments and grades, which allayed many of their fears. But not all.

When I had my students online, I asked them about their experience. Here is what an international graduate student said:

While we miss the in-person connections with other students and our professors, going online was not really a problem. When I delivered a facilitated reading discussion, I found that I had more confidence due to my comfort with digital technology. I also found that there was more participation in class. Although in-person instruction is my preference, I found aspects of my online classes to be better than expected. In some cases, preferable to my in-person experience!

I also found the whole process fascinating. What we know is that our classes are filled with digital natives; that is, students who have always had technology in their lives. Taking ourselves, who might be described as digital immigrants, out of our comfort zone and letting students be our guides through this new digital world I found exciting and a little fun. It provided a flipped classroom of sorts where the students were doing some of the teaching, and we became the students. What could be more exciting?

Like many other postsecondary institutions, my university is offering its summer courses fully-online. There is also the likely possibility that fall classes similarly will be fully-online. Finishing off a term with online lectures is one thing. Moving to all courses, from beginning to end, being online is something all together different. The good news is we will all be doing it together.

Scary but fascinating!

-Clayton Smith

Best Colleges (2019). 2019 Online Education Trends Report. https://res.cloudinary.com/highereducation/image/upload/v1556050834/BestColleges.com/edutrends/2019-Online-Trends-in-Education-Report-BestColleges.pdf

Cook, J. (2018). Online education and the emotional experience of the teacher. New Directions for Teaching and Emotion. DOI: 10.1002/tl.20282

Ginder, S. A., Kelly-Reid, J. E., & Mann, F. B. (2017). Enrollment and employees in postsecondary institutions, fall 2016; and financial statistics and academic libraries, fiscal year 2016. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018002.pdf

Johnson, N. (2019). Tracking online education in Canadian universities and colleges: National survey of online and digital learning 2019 national report. https://onlinelearningsurveycanada.ca/publications-2019/

Magda, S. J., & Smalec, J.S. (2020). Student perspectives on online programs: A survey of learners supported by Wiley Education Services. Louisville, KY: Wiley edu, LLC. https://edservices.wiley.com/student-perspectives-on-online-programs/

Thomson, C., & Esses, V. (2016). Helping the transition: mentorship to support international students in Canada. Journal of International Students, 6(4), 873-886. http://ojed.org/index.php/jis/article/view/323/247

Taking My Breath Away!

Throughout the summer, it has been my pleasure to enjoy working with two wonderful undergraduate students, Miranda Pecoraro and Renan Paulino. Each contributed in meaningful ways to our ongoing research projects that are examining student views on the promising practices for teaching linguistically and culturally diverse post-secondary international students.

Miranda Pecoraro is a third-year Social Work student from Windsor, Ontario who is in our Outstanding Scholars program. She has been working with me for the past three semesters. The Outstanding Scholars program “provides an exceptional and supportive undergraduate learning experience for high-achieving students, emphasizing depth and breadth of research-based academic inquiry, strong and ongoing faculty/student mentorship, effective communication of research achievement, and achievement of external recognition of academic excellence.” Check out this video where Outstanding Scholar students explain the OS program in their own words.

Renan Paulino is a third-year Education student from Brazil who joined us as part of the Mitacs Globalink Research Internship program, which places undergraduate students at Canadian universities from a wide variety of countries (e.g., Brazil, China, European Union, Germany, India, Israel, Mexico, UK, US) to engage in faculty-led research projects. The focus of the Mitacs program is to create awareness of the leading research being done at Canadian universities and to enhance linkages between top international students and Canadian university faculty members. Here is a video on the Mitacs Canada Globalink Research Internship program. Interestingly, this is Renan’s second international exchange in Canada (the first was in St. Johns, Newfoundland while he was a high school exchange student), and he is considering returning for graduate education in the near future…hopefully with us!

Miranda Pecoraro and Renan Paulino

Undergraduate research is one of the “high-impact practices,” originally identified by George Kuh (2008), that can be life-changing. They “demand considerable time and effort, facilitate learning outside of the classroom, require meaningful interactions with faculty and students, encourage collaboration with diverse others, and provide frequent and substantial feedback.” Students who participate in high-impact practices experience a more complete university student experience. Those that engage in undergraduate research frequently develop strong relationships with student peers and faculty members.

Our students participated in writing projects that led to a peer-reviewed published book chapter and research poster, and a journal article in press on the topic of “Variability by Individual Student Characteristics of Student Satisfaction with Promising International Student Teaching Practices.” They also developed a workshop on this topic for our upcoming University of Windsor GATAcademy. Further, they are facilitating an international student-learning community project that is continuing to investigate the difference in student opinions between STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and non-STEM students on this topic.

They really take my breath away!

I cannot wait to welcome more undergraduate students into our research group!

Clayton Smith

References:

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Smith, C., Zhou, G., Potter, M., & Wang, D. (2019). Connecting best practices for teaching linguistically and culturally diverse international students with international student satisfaction and student perceptions of learning. In James, W. B., & Cobonoglu, C. (Eds.), Advances in Global Education and Research Volume 3, (252-265). Sarasota, FL: Association of North America Higher Education International. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/educationpub/24/

Smith, C., Zhou, G., Potter, M., & Wang, D. (2019). Connecting best practices for teaching linguistically and culturally diverse international students with international student satisfaction and student perceptions of learning. Poster presented at the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Conference, Winnipeg, MB.

Finding the Connection

Colleges and universities in the U.S. and Canada are increasingly becoming ethnoculturally and linguistically diverse which is partially due to increasing enrolment of international students. Currently, 1.4 million international students choose to study at Canadian and U.S. post-secondary educational institutions, which increased by 7.1 percent between 2015 and 2016 (Canadian Bureau of International Education, 2016; Institute of International Education, 2016).

Currently, campus internationalization initiatives focus primarily on external areas including education abroad and student exchange, recruiting international students, and institutional partnerships. However, this is expected to change as more institutions are developing academic-related internationalization initiatives (e.g., international or global student learning outcomes, related general education requirements, foreign language requirements). A growing number of institutions are increasing faculty engagement in internationalization efforts. To do this, faculty will need to critically examine their role in campus internationalization and implement teaching strategies that address international student success factors.

In a recent study, we explored the promising teaching practices for teaching linguistically and culturally-diverse international students by identifying the teaching practices that have high levels of international student satisfaction and student perceptions of learning. This study is based on the belief that the most effective teaching practices are where promising teaching practices, student satisfaction, and student perceptions of learning meet.

We found that the promising teaching practices identified as having high levels of student satisfaction also have medium/high student perception levels of learning. We also found a positive correlation between student satisfaction and student perceptions of learning for each of the promising teaching practices. In particular, fourteen correlations were reported at the .700 level or higher, suggesting a strong positive correlation, including assessing needs, assignments, clarifying expectations, class preparation, culturally-responsive teaching, feedback, and language proficiency. Our hope is that faculty who engage in these teaching practices will become more engaged in campus internationalization and improve international student success on their campuses.

We are currently engaged in a student-informed research project that will see us compare international student satisfaction for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and non-STEM international students to learn more about why STEM and non-STEM students have different views on the effectiveness of the promising teaching practices.

For more information and to follow our project, here is the link to our research web page.

Yours internationally,

Clayton Smith

References

Canadian Bureau of International Education (2016). A world of learning: Canada’s performance and potential in International education. Ottawa: CBIE.

Institute of International Education (2016). Open doors 2016. New York, NY: IIE.

Recent Comments