Home » University Teaching

Category Archives: University Teaching

Meeting the International Student Enrolment Challenge with Enhanced International Student Engagement

Canada has seen a 29% increase in international students attending higher educational institutions, from 2022 to 2023, which has followed a 63% growth over the previous five years and more than 200% over the last decade (CBIE, 2023). This, however, is changing. Universities Canada (The Canadian Press, 2024) reports that enrolment of international students fell in 2024, in some cases by more than 50%, below the international student visa cap set by the federal government. Given this trend, we must ensure academic success and beneficial, appropriate, and resourceful study conditions for the international students studying at our institutions. One of the best ways of doing this is by enhancing international student engagement. In this blog, I introduce this topic and discuss ways we can all increase the engagement of international students in our classrooms.

International student engagement is international students’ active, ongoing effort to navigate and mediate the expectations and practices of their new academic environment (Kettle, 2017; Zimmerman, 2021). This concept views engagement as a social practice, where students interact with and respond to various elements such as actions, interactions, objects, values, expectations, and language. It emphasizes the students’ roles as active participants and experts in their own educational experiences, highlighting their strategies to adapt, succeed, and contribute to their academic and social environments. International scholarship on teaching and learning research shows that when international students feel connected and supported, they are more likely to dive into classroom activities, perform better academically, and build positive relationships with classmates and instructors (Freeman et al., 2014; Glass et al., 2015), and that engagement in the classroom is the strongest predictor of cognitive development for international students (Grayson, 2008).

Four interrelated types of engagement occur during learning activities, including behavioural, emotional, cognitive, and agentic engagement (Christenson et al., 2012). Behavioural engagement has been defined as participation in various activities (Finn, 1989), students’ positive effort, attention, and involvement in school (Skinner et al., 2009), and adaptive and maladaptive behaviour (Martin, 2010). Emotional engagement is generally conceptualized as comprised of positive and negative feelings toward school, teachers, and peers (Fredericks et al., 2004). Cognitive engagement has been described as beliefs and values about the importance of school and learning (Appleton et al., 2008; Martin, 2007) and self-regulation, strategy use, goals, and exerting effort (Martin, 2007). Agentic engagement is when individuals try to actively enrich their learning experiences and take responsibility for them (Reeve & Tseng, 2011).

Sense of belonging in a higher-educational setting significantly impacts the engagement of international students (Cena et al., 2021; Glass et al., 2015). Previous studies have shown that international students report a lower sense of belonging than native students (Strayhorn, 2012; Van Horne et al., 2018), and that the type and amount of extracurricular/social involvement are related to the sense of belonging (Bowman et al., 2019; Maestas et al., 2007), with more frequent participation in extracurricular activities increasing the sense of belonging to the institution (Thies & Falk, 2023). International students who feel integrated into the university community through meaningful interactions are more likely to participate in social activities (Glass et al., 2015).

Engagement is also affected by students’ unwillingness to communicate, which is the long-term tendency to avoid and/or devalue verbal communication (Kadi & Madini, 2019). Several factors related to anxiety have been identified, including concerns that limited English-speaking proficiency can inhibit clarity (Aksak & Cubucken, 2020; Horwitz et al., 1986), fear of being humiliated (Chichon, 2019; Wen & Cle ́ment, 2010), lack of self-confidence (Kadi & Madini, 2019; Saadat & Mukundan, 2019), anxiety over potential errors (Kang, 2005), instructors’ excessive emphasis on grammar (Wen & Cle ́ment, 2003; Woodrow, 2006), and place of origin (Woodrow, 2006). Several motivation and related factors have been identified as engagement influencers, including personality (Hz, 2022; Mohammadian, 2013), discussion topic (Kang, 2005; Zhou et al., 2021), grade evaluation approach (Zhou et al., 2021), family support (Aksak & Cubucken, 2020; Aydin, 2017), and socialization demands (MacIntyre et al., 1998).

Institutional policies and practices, such as inclusive teaching practices, culturally sensitive curricula, and opportunities for social interaction, play a pivotal role in fostering student engagement (Glass et al., 2015). Instructors can engage in strategies to enhance in-class communication, including shaping a positive classroom environment that can relax international students and reduce their anxiety (Smith et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2021), developing workloads appropriate for international students (Zhou et al., 2021), adopting collaborative teaching approaches (Lee et al., 2019; Saadat & Mukundan, 2019; Zhou et al., 2021), involving students in peer teaching (Freemen et al., 2015; Yamauchi et al., 2016), engaging in problem-based learning to encourage students to solve real-world problems in collaborative settings (Freemen et al., 2015; Yamauchi et al., 2016), using group discussions for students to articulate their understanding, ask questions, and learn from their peers (Freemen et al., 2015; Yamauchi et al., 2016), preparing before class to expand their knowledge of students’ cultural backgrounds and traditions (Riasati, 2012; Zhou et al., 2021), conducting warm-up activities at the beginning of class (Zhou et al, 2021), applying supportive practices (Kinsella, 1997; Smith et al., 2019), and using culturally-responsive teaching methods (Gay, 2010; Zhou et al., 2017).

So, while we could lament the current decrease in international student enrolment facing most Canadian post-secondary educational institutions, there is much we can and should do to increase international student engagement leading to higher levels of success for those students able to enrol at our institutions despite the current regulatory approach to cap international student enrolments.

References:

Aksak, K., & Cubukcu, F. (2020). An exploration of factors contributing to students’ unwillingness to communicate. Journal for Foreign Languages, 12(1), 155-170. https://doi.org/10.4312/vestnik.12.155-170

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 369-386.

Aydın, F. (2017). Willingness to communicate (WTC) among intermediate-level adult Turkish EFL learners: Underlying factors. Journal of Qualitative Research in Education, 5(3), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.14689/issn.2148-2624.1.5c3s5m

Bowman, N, A., Jarratt, L., Jang, N., & Bono, T. J. (2019). The unfolding of student adjustment during the first semester of college. Research in Higher Education, 60(3), 273-292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9535-x

Canadian Bureau of International Education (2023). International students in Canada, https://cbie.ca/infographic/

Cena, E., Burns, S., & Wilson, P. (2021). Sense of belonging and intercultural and academic experiences among international students at a university in Northern Ireland. Journal of International Students, 11(4), 812-831. https://www.ojed.org/index.php/jis/article/view/2541

Chichon, J. (2019). Factors influencing international students’ willingness to communicate (WTC) on a pre-sessional programme at a UK university. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 39, 87-96.

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Springer Nature. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-031-07853-8.pdf

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59, 117 – 142.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Glass, C. R., Kociolek, E., Wongtrirat, R., Lynch, R. J., & Cong, S. (2015). Uneven Experiences: The Impact of Student-Faculty Interactions on International Students’ Sense of Belonging. Journal of International Students, 5(4), 353-363. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1125097.pdf

Grayson, J. P. (2008). The experiences and outcomes of domestic and international students at four Canadian universities. Higher Education Research & Development, 56, 473-492.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern language journal, 70(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

Hz, B. I. R. (2022). Exploring students’ public speaking anxiety: introvert vs extrovert. Journal of English Language Studies, 7(1), 107–120. https://jurnal.untirta.ac.id/index.php/JELS/article/view/14412/8831

Kadi, R. F., & Madini, A. A. (2019). Causes of Saudi students’ unwillingness to communicate in the EFL classrooms. International Journal of English Language Education, 7(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijele.v7i1.14621

Kettle, M. (2017). International student engagement in higher education: Transforming practices, pedagogies and participation (pp. 5, 09-11, 13, 12, 11). Multilingual Matters. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/103570/22/103570.pdf

Kinsella, K. (1997). Creating an enabling learning environment for non-native speakers of English. In A. I. Morey, & M. K. Kitano (Eds.), Multicultural course transformation in higher education: A broader truth (pp. 104-125). Allyn and Bacon.

Lee, J. S., & Lee, K. (2019). The role of self-efficacy, task value, and learning goal orientation in willingness to communicate in a second language. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 40(2), 140-156.

Lee, J. S., Lee, K., & Chen Hsieh, J. (2019). Understanding willingness to communicate in L2 between Korean and Taiwanese students. Language Teaching Research, 26(3), 455-476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168819890

Macintyre, P. D., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a l2: A situational model of l2 confidence and affiliation. The Modern Language Journal, 82(4), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x

Maestas, R., Vaquera, G. S., & Zehr, L. M. (2007). Factors impacting sense of belonging at a Hispanic-serving institution. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 6(3), 237-256. http://doi.org/10.1177/1538192707302801

Martin, A. J. (2007). Examining a multidimensional model of student motivation and engagement using a construct validation approach. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 413-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000709906X118036

Mohammadian. T. (2013). The effect of shyness on Iranian EFL learners’ language learning motivation and willingness to communicate. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(11), 2036-2045. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.3.11.2036-2045

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

Riasati, M. J. (2012). EFL learners’ perception of factors influencing willingness to speak English in language classrooms: A qualitative study. World Applied Sciences Journal, 17(10).

Saadat, U., & Mukundan, J. (2019). Perceptions of willingness to communicate orally in English among Iranian PhD students. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 8(4), 31-44. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.8n.4p.31

Skinner, S., Kindermann, T., & Furrer, C. (2009). A Motivational Perspective on Engagement and Disaffection Conceptualization and Assessment of Children’s Behavioral and Emotional Participation in Academic Activities in the Classroom, Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493-525.

Smith, C., Zhou, G., Potter, M., & Wang, D. (2019). Connecting Best Practices for Teaching Linguistically and Culturally Diverse International Students with International Student Satisfaction and Student Perceptions of Student Learning, Advances in Global Education and Research Volume 3 (James, W. B., & Cobonoglu, C., Eds.), pp. 252-265. Association of North America Higher Education International.

Strayhorn, T. L. (2012). Sentido de pertenencia: A higherarchical analysis predicting sense of belonging among Latino college students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 7(4), 30-320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192708320474

The Canadian Press (2024, August 30). International student enrolment drops below federal cap: Universities Canada. National Post. Retrieved from https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/international-student-enrolment-drops-below-federal-cap-canada?taid=66d1bed289440d0001d0b514&utm_campaign=trueanthem&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter

Thies, T., & Falk, S. (2023). International students in higher education: Extracurricular activities and social interactions as predictors of university belonging. Research in Higher Education, 2023. https://doi-org.ledproxy2.uwindsor.ca/10.1007/s11162-023-09734-x

Van Horne, S. V., Lin, S., A. M., & Jacobson, W. (2018). Engagement, satisfaction, and belonging of international undergraduates at U.S. research universities. Journal of International Students, 8(1), 351-374. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v8i1.169

Wen, W. P., & Clément, R. (2003). A Chinese conceptualisation of willingness to communicate in ESL. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 16(1), 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310308666654

Woodrow, L. (2006). Anxiety and speaking English as a second language. RELC Journal, 37(3), 308–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688206071315

Yamauchi, L. A., Taira, K., & Trevorrow, T. (2016). Effective instruction for engaging culturally diverse students in higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 28(3), 460-470.

Zhou, G., Liu, T., & Rideout, G. (2017). A study of Chinese international students enrolled in the master of education program at a Canadian university. International Journal of Chinese Education, 6(2), 210-235. https://doi.org/10.1163/22125868-12340081

Zhou, G., Yu, Z., Rideout, G., & Smith, C. (2021). Why don’t they participate in class? In V. Tavares (Ed.), Multidisciplinary Perspectives on International Student Experience in Canadian Higher Education (pp. 81-101). IGI Global, https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-5030-4.ch005

Zimmermann, J., Falk., S., Thies, T., Yildirim, H. H., Kercher, J., & Pineda, J. (2021). Spezifische Problemlagen und Studienerfolg internationaler Studierender [Specific challenges and study success of international students]. In M. Neugebauer, H.-D. Daniel, & U. Wolter (Eds.): Studienerfolg und Studienabbruch (pp.179–202). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-32892-4_8

Moving from Silence to Action: Race and Racism in Postsecondary Language Classrooms

Racism is present in postsecondary language classrooms throughout the world. Research shows that a connection exists between race and language teaching, but more importantly, racist and colonial foundations persist in the language classroom (Kubota & Lin, 2006). This can be seen through the classroom presence of epistemological racism, White supremacy, and social hierarchical power structures.

The new IGI Global book, Interrogating Race and Racism in Postsecondary Language Classrooms (Huo & Smith, 2024), takes an important step forward by investigating race and racism in postsecondary language classrooms, how race interacts with language, how power impacts and shapes language teaching and learning, and how hegemony and ideology perpetuate linguistic injustice and discrimination against racially minoritized students and instructors. It also examines how racism has created institutional, structural, and individual barriers for language teachers and learners in higher education. It does this by applying and integrating major theoretical frameworks, embracing various discourses, narratives, stories, and counter stories in different geographic and language teaching contexts, including a collection of liberatory and emancipatory anti-racist and anti-oppressive pedagogies in global postsecondary language teaching contexts, and using intersectionality between language and race to problematize raciolinguistic injustice and hierarchy.

As educators, we can not be silent on the presence of race and racism in postsecondary language classrooms. Instead, we should “examine the intersectionality of language and race to understand linguicism and the historical contextual basis that frames discourse around English language education, and how it interplays and intertwines with race, racial identity, and racialization” (Holden & Smith, 2024, p. 317).

-Clayton Smith

References:

Huo, X., & Smith, C. (2024). Interrogating race and racism in postsecondary language classrooms. IGI Global. doi: 10.4018/978-1-6684-9029-7

Kubota, R., & Lin, A. (2006). Race and TESOL: Introduction to concepts and theories. TESOL Quarterly,40(3), 471–493. doi:10.2307/40264540

Publication Calls on Educators to Create Inclusive Learning Spaces.

Interrogating Race and Racism in Postsecondary Language Classrooms

Language is power, in the hands of linguistic gatekeepers and the dominant class. From “coloniality of power” (Quijano, 2000) to “coloniality of language” (Veronelli, 2015, p. 113), English has become a “colonial language” (Kachru, 1986, p. 5) and a “language for oppression” (Kachru, 1986, p. 13), replacing the implementation of carrots and sticks in the colonial times in the form of instilling raciolinguistic ideologies of the centre into the periphery. Language is raced and race is languaged (Alim et al., 2016). Racialization, synonymous with racial classification, is a process of “Looking like a Language, Sounding like a Race” (Rosa, 2019). The racialization of language subjugates, subordinates, dehumanizes, and others people of colour.

Join us as we interrogate race and racism in postsecondary language classrooms in our upcoming IGI-Global book. We will use the perspective of intersectionality between language and race in higher education classrooms, by problematizing raciolinguistic injustice and hierarchy with the monolingual and monocultural norm as a frame a reference, combating racism, linguicism, native speakerism, and neo-racism, as well as calling for changes, emancipation, and pedagogical paradigm shifts so as to teach English for justice and liberation (Huo, 2020). This book will investigate race and racism in postsecondary language classrooms, how race intersects with language, how power impacts and shapes language teaching and learning, and how hegemony and ideology perpetuate linguistic injustice and discrimination against racially minoritized students. It will examine how racism has created institutional, structural, and individual barriers for language learners in higher education, as well as potential strategies to combat racism, linguicism, and neo-racism.

We ask prospective contributors to submit research-based and data-driven chapters to elicit stories, counter stories, garner racialized experiences and perspectives, and represent resistant voices through multiple research methods, including but not limited to interviewing, observation, discourse analysis, narrative inquiry, ethnography, journaling, focus groups, surveys, and case studies. Here is the Call for Proposals.

Recommended Topics

- Race, racialization, and racism

- Intersectionality between race and language

- Language and identity

- Linguicism and linguistic imperialism

- Monolingualism, native speakerism, and standardization

- Native-non-native dichotomy

- Power, hegemony, and hierarch

- Raciolinguistic ideology

- Neo-racism (i.e., based on nationalities, ethnicities, and cultures)

- Accentism

- Language diversity and linguistic rights

- Raciolinguistic justice and social justice

- Discourses and stories in different geographic and language teaching contexts across the globe

- Narratives and counter-narratives

- Barriers, challenges, and resistance

- Lived experiences

- Multilingualism, plurilngualism, and translanguaging

- Anti-oppressive and decolonizing language policies

- Anti-racist and anti-colonial pedagogies and practices

- Critical pedagogies in global higher education language teaching contexts

- Ethical internationalization in postsecondary language classrooms

This book is intended for scholars, researchers, faculty, instructors, and professionals in English language teaching, higher education, language education, applied linguistics, sociolinguistics, educational linguistics, anti-racist education, critical multilingual studies, translingual studies, and those who are interested in the research of race, language, and the area of teaching English cross-culturally and translingually in higher education classrooms, such as faculty and instructors, educational developers who design the inclusive, anti-racist, and anti-colonial curriculum, and administrators and policymakers who oversee academic, especially language programs. The book will also be useful for teacher candidates, non-native English-speaking students, undergraduates, and graduate students in TESOL/ESL, second language acquisition, and higher education programs.

Important Dates

- March 31, 2023: Proposal Submission Deadline

- April 14, 2023: Notification of Acceptance

- May 14, 2023: Full Chapter Submission

- June 27, 2023: Review Results Returned

- August 8, 2023: Final Acceptance Notification

- August 22, 2023: Final Chapter Submission

If you would like to discuss a potential book chapter idea, contact us at raceandlanguage@gmail.com.

-Xiangying Huo (University of Toronto) and Clayton Smith (University of Windsor)

References

Alim, S., Rickford, J. R. & Ball, A. F. (Eds.) (2016). Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Huo, X. Y. (2020). Higher education internationalization and English language instruction: Intersectionality of race and language in Canadian universities. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-60599-5

Kachru, B. B. (1986). The alchemy of English: The spread, functions and models of non-native Englishes. Pergamon.

Quijano, A. (2000). The coloniality of power and social classification. Journal of World-Systems Research 6(2), 342-386.

Rosa, J. (2019). Looking like a language, sounding like a race: Raciolinguistic ideologies and the learning of Latinidad. Oxford University Press.

Veronelli, G. A. (2015). Five: The coloniality of language: Race, expressivity, power, and the darker side of modernity. Wagadu: a Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies, 13, p. 108-134.

Teaching Through the Screen

Earlier this week, during the virtual Fierce Education conference titled, Higher Education: Helping Faculty Navigate top Challenges in this New Blending Learning Environment, I had the opportunity to take in a talk presented by Sean Michael Morris, vice-president, academics at Course Hero. In his presentation, “Teaching through the Screen: Engaging Imagination to Engage Students,” Sean spoke about critical pedagogy as a humanizing pedagogy; that our focus should be on “seeking the human behind the screen, the human behind the bureaucracies of education, the human behind behaviorist technologies.” So, put another way, we should not teach to the screen (after all it is just a digital tool!), but look through it to those behind the screen who we are teaching. Only by changing our perception of online learning will we be truly able to engage our students. Wow, what a revelation!

Looking into the distance at the Cliffs of Moher, Ireland

Sean introduced us to Maxine Green who wrote in 2000 that “Our obligation today is to find ways of enabling the young to find their voices, to open their spaces, to reclaim their histories in all their variety and discontinuity” (Releasing the Imagination, 120). Imagination, as a “practice of freedom,” can inspire us to change the way we reach our learners. With the COVID-19 experience and our two-year pivot to online learning, this is more needed today than ever.

He then reminded us of what Jesse Stommel said about starting by trusting our students and emphasized that students are producers of knowledge, not just consumers of knowledge. Remembering that the more we know, the less we imagine, can be a powerful learning concept. Engaging students in a learning partnership is empowering for both learners and instructors. In a 2014 interview, Stommel commented:

Learning is always a risk. It means, quite literally, opening ourselves to new ideas, new ways of thinking. It means challenging to engage the world differently. It means taking a leap, which is always done better from a sturdy foundation. This foundation depends on trust – trust that the ground will not give way beneath us, trust for teachers, and trust for our fellow learners in a learning community.

-Jesse Stommel

So, what if we trusted our students as co-learners and used our imagination to see through the screen?

While this may have been true pre-pandemic, it is even more true now. The days of students coming to us to attend in-person classes in university lecture halls have probably changed. An increasing number of students will probably be seeking online courses, be they synchronous, asynchronous, or blended. They will be the new traditional learners in post-secondary or tertiary learning. We will need to trust them and encourage their learning by “seeking the human behind the screen.”

I am ready!

-Clayton Smith

Taking Time to Ponder

Harvard psychology professor Ellen Langer said something on this week’s Sunday Morning news show that caught my attention and put me on a reflective path.

Langer said that human beings are unique in their ability to think about the future, which leads us to be thinkers about our unique and collective futures (Weisfogel & Ross, 2020). While recognizing that plans create an illusion of control and that plans are guesses, these uncertain times call for us to contemplate and hope about what is to come. Langer goes on to say, “But what we need to recognize is that if something leads us in a different direction, that could end up even better for us.” So, in other words, by taking time to ponder, we each may be able to find a pathway toward a different but perhaps more enjoyable destination.

I thought about this all day.

Since returning to teaching four years ago, I have focused my research in three areas. First, I have continued my career-long work in critically assessing the impact of Strategic Enrolment Management on the twin goals of achieving institutional health and student success. Second, I renewed my interest in the international student experience by exploring student perspectives on the way we teach in our colleges and universities and how we can improve our teaching of culturally and linguistically diverse international students. Third, after coauthoring two open educational resource (OER) textbooks and making increasing use of OERs in my teaching, I am beginning to focus on how we can achieve deep and interdisciplinary learning by enhancing our use of OERs.

While each of these research threads are different, it occurred to me that there is common ground between them; namely, the amplification of the student voice. If ever there was a time to pay more attention to student views, it is now. The COVID-19 Pandemic has left so many of us questioning the future. This includes students, faculty and staff, and those who lead our postsecondary educational institutions.

Psychiatrist Pavan Madan, who was also interviewed on Sunday Morning, spoke about the anxiety that is impacting us all. Dr. Madan suggests that “we put our big dreams aside for now and focus on the small, more manageable details of daily life” (Weisfogel & Ross, 2020).

So, in this public space, let me say that during the balance of the time we have in the Pandemic and for the time to follow, I will commit to amplifying the student voice in all I do.

If this interests you, consider joining me (Clayton.Smith@uwindsor.ca). I am thinking that both the journey and the destination will be quite enjoyable.

Clayton Smith

Weisfogel, A. & Ross, C. (27 December 2020). Going to Plan B: When COVID pulls the rug out from under you. Sunday Morning. New York: CBS. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/going-to-plan-b-when-covid-pulls-the-rug-out-from-under-you/?ftag=CNM-00-10aab8c&linkId=108041071

Empathy Matters

At this year’s U.S. Democratic National Party Convention, empathy took centre stage as former vice-president Joe Biden accepted his party’s nomination to be its candidate for president of the United States. Each of his endorsers touted Biden’s “ability to connect with what someone else is feeling and pointed to that characteristic as making him uniquely qualified to lead the country, particularly during a time of crisis like the coronavirus pandemic” (Merica, 2020, para 2). Words like honesty, humility, empathy, and grace were heard from many of the convention speakers, including U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren and former President Barack Obama, both of whom know something about achieving change during a crisis.

While introducing my first-year fall 2018 EDUC 1199 Teaching and Learning (Part One) students to various perspectives on the year one classroom observation field experience, we heard Ms. Bridget Russo, a retired principal in the Windsor-Essex Catholic District School Board say something that I have shared with each of my classes since. The question posed to the panel was this: “What advice do you have for first-year Concurrent Education students as they embark on their first field experience?” Ms. Russo said, “show empathy.” She reflected that of all the things that students bring to their field experience, the most important is empathy. With it, so much can be accomplished. Without it, nearly nothing can be achieved.

These two events, while vastly different, point to the importance of empathy in our time. But what is empathy and why is it so important?

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines empathy as

“the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another of either the past or present without having the feelings, thoughts, and experience fully communicated in an objectively explicit manner.”

Sometimes there can be confusion between empathy and compassion. Compassion refers broadly to sympathetic understanding, while empathy is the ability to relate to another person’s pain as if one has experienced that pain themselves. It involves seeing their world, appreciating them as human beings, communicating understanding, and understanding feelings (Sahota and Lewitz, 2014).

So, in the case of the crises currently facing the U.S., empathy would be the ability to relate to being a victim of the coronavirus or racial inequality. In the case of teacher candidates attending their first field experience, empathy would be the ability to connect with students in or near the classroom setting, some of whom are experiencing significant challenges while others are impacted by various barriers to their own learning.

As the doors to the academy open this week, let me suggest that each of us reach deep within our hearts, minds, and souls to find empathy for all those we meet. Each of us faces our own challenges, and it is so important that those we come in contact understand a little of what each of us is going through.

The Avatar (2009) film captures this well when Neytiri says to Jake and Jake says to Neytiri “I see you.” This means when you see me you bring me into existence.

I’ve got to think that by seeing the people we meet, we can make a difference in their lives and in our lives too.

So, empathy really matters!

References:

Merica, D. (2020, April 15). ‘Empathy matters’: Joe Biden’s endorsers highlight the same trait. CNN Politics. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/15/politics/joe-biden-empathy/index.html

Sahota, M., & Lewitz, O. (2014). Co-aching: How to use compassion to transform your effectiveness. Agile Alliance Conference, Orlando, FL.

Playing Your Position

While attending the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Conference recently, I attended a session in which Melanie Hamilton and Bonnie Farries, from Lethbridge College, spoke about the intersection of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) and Strategic Enrolment Management (SEM).

These are two areas that rarely find their way to the same platform, either at a professional or an academic gathering.

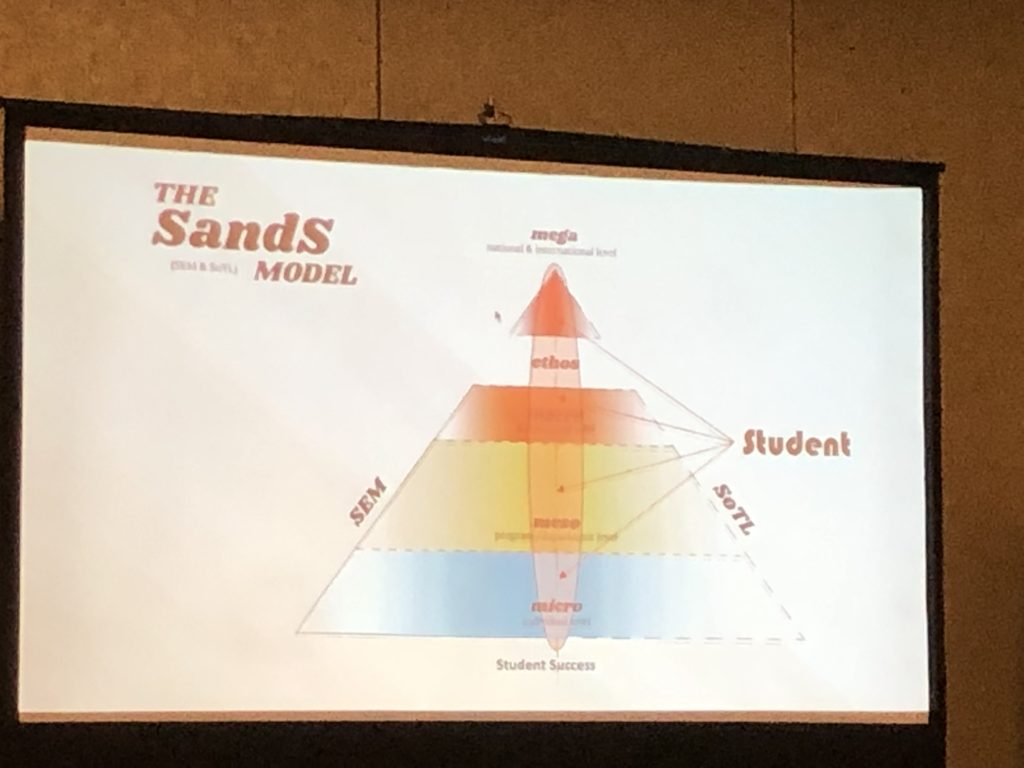

Hamilton and Farries introduced a model to show how each of these desparate activities support overall student and institutional success. The model they shared at the conference is below. Hamilton and Farries argued that SEM focuses on macro level decision-making without sufficient attention to the micro level and SoTL focuses on the micro level with little attention paid to macro level priorities. Through effective coordination, SEM and SoTL can enhance macro and micro activities to achieve greater levels of student success.

My take away is that both SoTL and SEM play an important and effective role in institutional effectiveness and student success.

The maxim of “playing your position” seems appropo to the intersection between SEM and SoTL. Many have written about the importance of playing your position within the context of team. Vince Lombardi said, “Individual commitment to a group effort–that is what makes a team work, a company work, a society work, a civilization work.” Andrew Carnegie commented, “Teamwork is the ability to work together toward a common vision. The ability to direct individual accomplishments toward organizational objectives. It is the fuel that allows common people to attain uncommon results.” And Helen Keller professed “Alone we can do so little, together we can do so much.” All could be said to endorse the notion of each of us playing our position well; that by performing our role effectively, we can achieve great things.

If enrolment professionals and the instructors who teach our classes each perform their respective roles well, it is likely that we will achieve much institutional and student success.

Clayton Smith

Ireland Take-Aways

While in Ireland last week, I became aware of the concept of “take-aways” rather than the North American term “to-go,” and so I thought I would reflect on a few take-aways from our recent, mostly sunny, trip to Ireland.

Let me start with my reason for visiting the emerald isle.

I had the pleasure of presenting a paper on some research my research team has recently completed on “Connecting Best Practices for Teaching Linguistically and Culturally-Diverse International Students with International Student Satisfaction and Student Perceptions of Learning” at the Ireland International Conference on Education, which was held in Dún Laoghaire, Ireland, a short distance from Dublin. It was well received and left me reflecting on how I might collaborate with researchers in other countries on this topic. So many are interested in learning more about how we might provide a student voice in our research on the practices for teaching international students.

This is a small conference (about 100 participants) that left me with a developing network of research colleagues from around the world–all with an interest in enhancing education within the post-secondary education sector. Here are a few highlights:

- Gabriel-Miro Muntean, from Dublin City University spoke about the EU Horizon 2020 NEWTON Project’s use of innovative technologies and enhanced learning methods and tools to create or inter-connect existing state-of-the-art teaching labs and to build a pan-European learning network platform to encourage more students to consider STEM careers. While only a few years in, it shows great potential for turning on a new generation or STEM scientists and practitioners.

- Michael Plummer, from MAPco Education Consultant Group, shared a bit about misguided public criticism of education, and special education in particular. Findings from his study revealed that there is a continuing lack of knowledge by the public on the issues around special education. He also said “You can teach about the profession, but you cannot teach someone how to be a teacher. Teaching is a complex art, and not everyone can do it.” Very powerful stuff. Really made me think about the individual characteristics that contribute to inspired teaching.

- Deborah Patterson and Susan Carlile, from Portland State University, intrigued us with a session called “Nags, Bitches and Beauties: Women in Leadership” in which they shared the challenges facing women leaders, and recommended development of formal and informal mentoring program, use of a network of support within and outside the organization, and increased training for allies. I have seen many of these challenges first hand, and was impressed with their body of research. Hopefully, it will lead to action in the academy to enhance the way we support women along the way to leadership roles.

- Adam Unwin, from University College London, spoke about some themes from his book with John Yandell, Rethinking Education: Whose Knowledge is it Anyway? In particular Unwin stressed the challenges associated with the impact of Neoliberal measurement approaches, which have done a lot to “deform the landscape of schooling” in the United Kingdom. It made me reflect on how we can address this approach as the Ontario Government pushes performance funding within the post-secondary sector in the next several years. He even gave me a copy of his book!

But you can’t just go to Ireland for work, so we also took in some of the sights.

We toured the Wicklow Mountains, otherwise known locally as the Dublin Mountains, which borders the counties of Dublin, Wexford, and Carlow. Of course, they really are not mountains. Our tour guide told us at 561 meters, they are not tall enough to be mountains. But are they ever beautiful and mountain-like!

We also visited the western part of the country and took in side trips to Cliffs of Moher and the City of Galway. The Cliffs of Moher are really impressive. They stretch eight kilometers, reaching a height of 214 meters, with a vista embracing the Aran Islands. Almost thought I was in Newfoundland. The warm–we were told they are not always warm–winds whipping across the landscape took us back to the Harry Potter films, one of which was filmed here.

Galway is wonderful. Full of cultural charm, with lots of shopping and, of course, more restaurants and pubs than one can count.

Then there is Dublin itself. So much history with the experience of nationhood so near the surface of many conversations. Some of what tops the list include Dublin Castle, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Christ Church, the National Museum of Ireland, St. Stephen’s Green, Trinity College, and the huge Phoenix Park that includes the Dublin Zoo, home to some very famous lions.

Our tour guides (two of the three were named John) used a wonderful style of speaking that I think I will try to use more in my teaching. Basically, they introduced what we would do, then told a story or two about what we would see, and then summarized before moving on to a new slice of the tour. Then, at the end, they shared some of the highlights. While it may be something that is just present in the Irish approach to interpersonal communications, it really worked, and was enjoyed by everyone.

Perhaps our true take-aways centre on the people, including the colleagues we met at the conference along with the native Irish we came to embrace through our travels in this breath-taking land.

I think we will be coming back.

Clayton Smith

Potluck, Posters, & Loads of Fun

For the past few semesters, I have ended my smaller classes with potluck food and beverage sharing, a poster fair, and a chance to end the semester with loads of fun. I thought I’d share a bit about this in case this may be something other teachers might want to try.

The students plan the potluck. I just ask that they try to mix it up a bit so we don’t get all chips and poutine! This year students brought food items in from their home culture, as well as what could readily be found in nearby bakeries and grocery stores. What is important is that everyone contribute. The added benefit is that there is almost always food left over, and this results in the sharing continuing even after class finishes. I see the potluck as a key outcome of the course. Students will engage with each other (and me!) around the potluck table in some wonderfully engaging ways.

The poster fair is a great match for any class in which a major project is completed. I have done it for my Research in Education Class, a first-year graduate level class in which students prepare a research proposal. Students in my Theories of Individual and Collective Learning, an undergraduate course in our Minor in Organizational Learning and Teaching, also prepare posters. During the poster fair, students listen to each other’s poster presentations and provide peer review at the end, including an opportunity to engage collectively in a topic of the individual students’ choice. It is a great reflective experience that provides students with a truly authentic learning experience.

The loads of fun part comes as we engage each other, take a class photo, and then assemble an end-of-class mind map on the class topic. Lots of moving around, wonderful smiles, and a chance to put the course into practice.

You might think this approach is best with one type of student or class. Actually, it works for undergraduate and graduate classes. Size matters, with the best results being when the students know each other. But my guess is it could also work in a larger class. Maybe I will try that next year!

Clayton Smith

Finding the ePortfolio Magic

This year, I began teaching and advising first- and second-year students in our Concurrent Education program. This program allows students to earn two bachelor degrees in five years, one in an academic major, and the other in education. Education courses are taught in each year of the program.

One of the outcomes early on in this program is the creation of an educational portfolio or ePortfolio.

Students document their learning throughout the program using an ePortfolio. When finished, they will have an ePortfolio that shows how they meet the Ontario College of Teachers’ (OCT) professional standards. It will also contain their teaching philosophy, and resume/cv. Rather than the customary cover letter, an ePortfolio helps students to present a bit of themselves in a visually appealing format. This is something that is becoming an essential part of the process of becoming a professional teacher.

But it is much more than that.

I know this because I created my own ePortfolio. In it, you will find this blog, as well as other blogs I have written on teaching and related topics. You will also see that my focus is on teaching and research in a postsecondary educational setting, and so it has a slightly different feel than what my students are doing. I thought it was important that I develop one so that I would know some of the challenges in creating an ePortfolio. I also wanted to experience some of the fun too!

What I learned along the way is magical.

While much of what students do is to assemble artifacts (e.g., photos, documents, videos) that show how they meet the OCT professional standards. The magic arrives when they write reflections about these artifacts and share how they use them in their teaching.

Teachers, like most professionals, are all about doing.

They prepare lesson plans, design courses, conduct student assessments, lecture, and facilitate student learning in lots of wonderful ways. They are, put simply, busy with the practice of their craft.

What we are learning, however, is that the practice of reflective thought is essential for teachers to grow as educators, and to ensure they connect with their students.

Well-written ePortfolios include a reflective bit of writing (usually a paragraph or two) for each artifact. It is in writing reflections that students take a deep dive into their values, ethics, and ways of knowing that support their teaching. I am greatly enjoying reading the ePortfolios my students are creating.

This helped me understand what I have achieved with my teaching. It also helped me to establish some goals for where I want my teaching to go. Most importantly, it allowed me the freedom to dream about why I teach and how I help to make the world a little bit better by “teaching for learning.”

Magical indeed!

Clayton Smith

Recent Comments