Clicker Response Systems (CRS) are devices that allow students to respond to questions posed during a lesson. Plenty of literature has discussed the relation between CRS and improving grades (Gauci et al., 2009; Lui et al., 2017). However, the extent to which CRS actually promotes learning requires a qualitative exploration of how CRS may or may not add to students’ learning.

Creates commitment to answers: Encouraging students to use clickers means students are forced to commit to one answer. If a question is openly posed in class without requiring a direct answer, students may think “well it could be (a) but it could also be (b), and they wait for the correct answer to be revealed, but without giving critical thought to their response. Then the student compares the response they prepared in their head to the correct answer. When you factor in CRS, the student is forced to make one choice which makes them more susceptible to reasoning through the options and reflecting on why they think one response choice is the correct answer instead of another (Gauci et al., 2009).

CRS makes the invisible visible: Without a doubt, raising a hand to answer a question in a class can be intimidating. Whether it’s in a high-school classroom where students know each other, or in a hall of 300 university students who never sit in the same seat. Some students are comfortable with answering questions posed in class, while those who may shy tend to observe the engagement but not be a part of it. CRS helps alleviate the discomfort related to participating in class by allowing the student’s voice to be heard in a way that is within their comfort zone. CRS are especially useful for increasing fairness for the students uncomfortable with speaking in class in classes where participation is graded. A bonus is it keeps record of student participation, so the teacher does not have to.

Double Edge Sward of Clickers from Teachers’ perspective

Some may believe that interrupting the lesson for a quick polling might disrupts the flow of lessons, create a distraction that loses student’s attention, and is an ineffective use of class time. Those who have these beliefs would argue that these types of questions are best left as an out-of-class activity that students should compete on their own time to test where they stand in their understanding. However, the use of CRS may bolster student’s learning in ways that the traditional teaching does not.

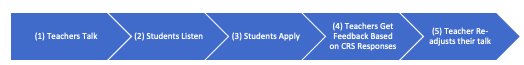

CRS may stop collateral damage: Teachers can review class performance collectively on each question posed during the lesson. Having information on which response option is being selected more often than another may give the teachers insight on how students are approaching the question. As such, CRS become a test of whether the teachers’ lessons are successfully and clearly communicating the material. This provides the teacher with an opportunity to reflect on why the information might be miscommunicated and how they can alter their teaching method. In traditional classrooms, the teacher would only have this feedback after giving a test that the majority of students may do poorly on. CRS feedback can spot problems in miscommunication and understanding before they have adverse grading outcomes (Lui et al., 2017).

The teacher could also see which students are having the most difficulty. Having this knowledge is extremely useful for smaller learning environments, such as high-school classes, because it allows the teacher to reach out to the students who may be in need of one-on-one sessions.

Diagram created through PowerPoint by Baher.T.

Creates learning in a different way: By using CRS, the student can attempt a question while the teacher is still in the room, which allows for questions to be asked and answers to be provided in real time. A student might pose an important question, that otherwise might not have been posed, because the question conveniently came up while the teacher is in the same room. That question can then benefit the entire class because the teacher could repeat and address the question aloud. That way, all students walk away with something learned about the question. The point being, anytime an teacher describes a phenomenon or clarifies something about the content being taught, learning is being facilitated.

Is the buck worth the bang?

Not everyone is tech savey. Learning how to set-up a CRS system may seem like a burden to some. Some students may feel undue pressure to purchase the clickers due to financial situations. Whatever the case may be, there are ways to extrapolate the methodology of CRS without having the system. Afterall, it is the ways in which the instructional tool is used that makes it effective, not the tool itself. teachers “put the learning in the tool”. As such, teachers could use other polling systems that allow students to submit answers through their phones.

Tabarak

References

Barr, R. B. and Tagg, B. (1995). From teaching to learning: A new paradigm

for undergraduate education. Change, 27(6), 13–25.

Chasteen, S. (n.d.). Explaining to your students why you’re using clickers. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NGx7EzDQ-lY

Gauci, S. A., Dantas, A. M., Williams, D. A., Kemm, R. E. (2009) Promoting

student-centered active learning in lectures with a personal response

system. Advances in Physiology Education 33(1): 60–71.

Liu, C., Chen, S., Chi, C., Chien, K.-P., Liu, Y., & Chou, T.-L. (2017). The Effects of

Clickers With Different Teaching Strategies. Journal of Educational

Computing Research, 55(5), 603–628.